http://www.wikipaintings.org/en/kazimir-malevich

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Kazimir_Malevich

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Kazimir_Malevich

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich (Russian: Казими́р Севери́нович Мале́вич [kɐzʲɪˈmʲir sʲɪvʲɪˈrʲinəvʲɪt͡ɕ mɐˈlʲevʲɪt͡ɕ], Polish: Kazimierz Malewicz, Ukrainian: Казимир Северинович Малевич [kazɪˈmɪr sɛwɛˈrɪnɔwɪtʃ mɑˈlɛwɪtʃ], German: Kasimir Malewitsch) (23 February 1879, previously 1878: see below – 15 May 1935) was a Russian painter and art theoretician. He was a pioneer of geometric abstract art and the originator of the avant-garde Suprematist movement.

Early life

Kazimir Malevich was born near Kiev in the Kiev Governorate of the Russian Empire (today Ukraine). His parents, Seweryn and Ludwika Malewicz, were ethnic Poles who had fled to Ukraine in the aftermath of the January Uprising of 1863 and he was baptised in the Roman Catholic Church. His father managed a sugar factory. Kazimir was the first of 14 children, only nine of whom survived into adulthood. His family moved often and he spent most of his childhood in the villages of Ukraine amidst sugar-beet plantations, far from centers of culture. Until age 12 he knew nothing of professional artists, though art had surrounded him in childhood. He delighted in peasant embroidery, and in decorated walls and stoves. He himself was able to paint in the peasant style. He studied drawing in Kiev from 1895 to 1896.

Later career

From 1896 to 1904 Kazimir Malevich lived in Kursk. In 1904, after the death of his father, he moved to Moscow. He studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture from 1904 to 1910 and in the studio of Fedor Rerberg in Moscow (1904 to 1910). In 1911 he participated in the second exhibition of the group Soyuz Molodyozhi (Union of Youth) in St. Petersburg, together with Vladimir Tatlin and, in 1912, the group held its third exhibition, which included works by Aleksandra Ekster, Tatlin and others. In the same year he participated in an exhibition by the collective Donkey&s Tail in Moscow. By that time his works were influenced by Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, Russian avant-garde painters who were particularly interested in Russian folk art called lubok. In March 1913 a major exhibition of Aristarkh Lentulov&s paintings opened in Moscow. The effect of this exhibition was comparable with that of Paul Cézanne in Paris in 1907, as all the main Russian avant-garde artists of the time (including Malevich) immediately absorbed the cubist principles and began using them in their works. Already in the same year the Cubo-Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun with Malevich&s stage-set became a great success. In 1914 Malevich exhibited his works in the Salon des Indépendants in Paris together with Alexander Archipenko, Sonia Delaunay, Aleksandra Ekster and Vadim Meller, among others.

Suprematism

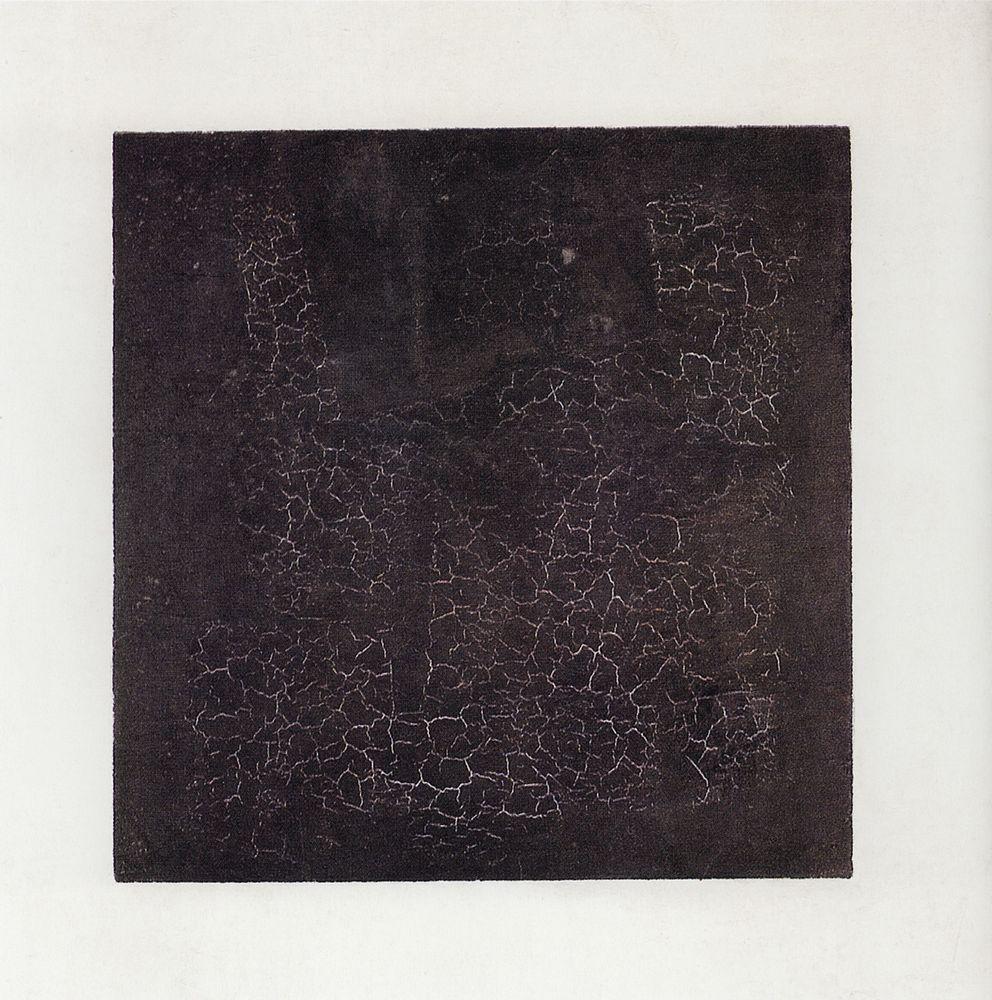

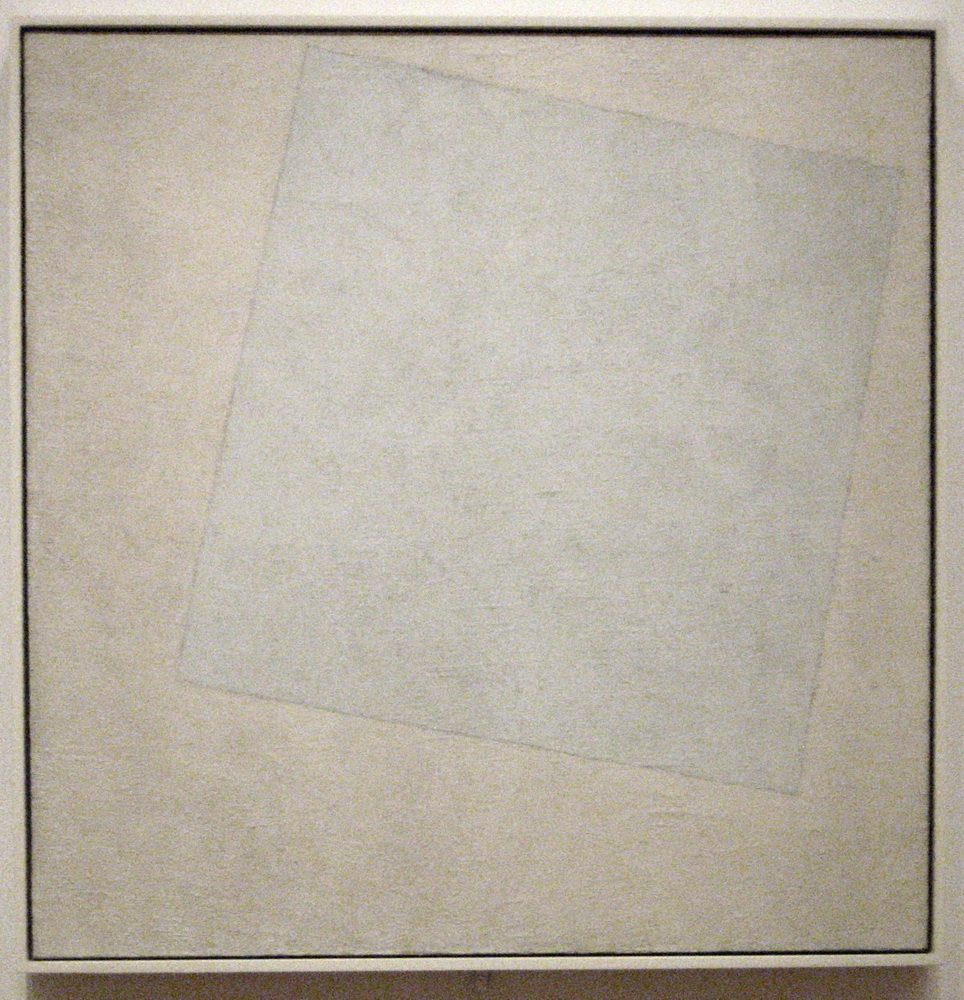

In 1915, Malevich laid down the foundations of Suprematism when he published his manifesto From Cubism to Suprematism. In 1915–1916 he worked with other Suprematist artists in a peasant/artisan co-operative in Skoptsi and Verbovka village. In 1916–1917 he participated in exhibitions of the Jack of Diamonds group in Moscow together with Nathan Altman, David Burliuk and A. Ekster, among others. Famous examples of his Suprematist works include Black Square (1915) and White On White (1918).

In 1918, Malevich decorated a play, Mystery Bouffe, by Vladimir Mayakovskiy produced by Vsevolod Meyerhold.

He was also interested in aerial photography and aviation, which led him to abstractions inspired by or derived from aerial landscapes. As Professor Julia Bekman Chadaga (now of Macalaster College ) writes:

In his later writings, Malevich defined the "additional element" as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception... In a series of diagrams illustrating the "environments" that influence various painterly styles, the Suprematist is associated with a series of aerial views rendering the familiar landscape into an abstraction... (excerpted from Ms. Bekman Chadaga&s paper delivered at Columbia University&s 2000 symposium, "Art, Technology, and Modernity in Russia and Eastern Europe")

Some Ukrainian authors claim that Malevich&s Suprematism is rooted in the traditional Ukrainian culture.

Post-revolution

After the October Revolution (1917), Malevich became a member of the Collegium on the Arts of Narkompros, the Commission for the Protection of Monuments and the Museums Commission (all from 1918–1919). He taught at the Vitebsk Practical Art School in the USSR (now part of Belarus) (1919–1922), the Leningrad Academy of Arts (1922–1927), the Kiev State Art Institute (1927–1929), and the House of the Arts in Leningrad (1930). He wrote the book The World as Non-Objectivity, which was published in Munich in 1926 and translated into English in 1959. In it he outlines his Suprematist theories.

In 1923, Malevich was appointed director of Petrograd State Institute of Artistic Culture, which was forced to close in 1926 after a Communist party newspaper called it "a government-supported monastery" rife with "counterrevolutionary sermonizing and artistic debauchery." The Soviet state was by then heavily promoting a politically sustainable style of art called Social Realism—a style Malevich had spent his entire career repudiating. Nevertheless, he swam with the current, and was quietly tolerated by the Communists.

International recognition and banning

In 1927, he travelled to Warsaw and then to Berlin and Munich for a retrospective which finally brought him international recognition. He arranged to leave most of the paintings behind when he returned to the Soviet Union. Malevich&s assumption that a shifting in the attitudes of the Soviet authorities towards the modernist art movement would take place after the death of Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky&s fall from power, was proven correct in a couple of years, when the Stalinist regime turned against forms of abstraction, considering them a type of "bourgeois" art, that could not express social realities. As a consequence, many of his works were confiscated and he was banned from creating and exhibiting similar art.

Critics derided Malevich&s art as a negation of everything good and pure: love of life and love of nature. The Westernizer artist and art historian Alexandre Benois was one such critic. Malevich responded that art can advance and develop for art&s sake alone, saying that "art does not need us, and it never did".

Malevich&s work only recently reappeared in art exhibitions in Russia after a long absence. Since then art followers have labored to reintroduce the artist to Russian lovers of painting. A book of his theoretical works with an anthology of reminiscences and writings has been published.

Death

Malevich died of cancer in Leningrad on 15 May 1935. On his deathbed he was exhibited with the black square above him, and mourners at his funeral rally were permitted to wave a banner bearing a black square. His ashes were sent to Nemchinovka, and buried in a field near his dacha. A white cube decorated with a black square was placed on his tomb. The city of Leningrad bestowed a pension on Malevich&s mother and daughter. "No phenomenon is mortal," Malevich wrote in an unpublished manuscript, "and this means not only the body but the idea as well, a symbol that one is eternally reincarnated in another form which actually exists in the conscious and unconscious person."

Posthumous sales

Black Square, the fourth version of his magnum opus painted in the 1920s was discovered in 1993 in Samara and purchased by Inkombank for $250,000. In April 2002 the painting was auctioned for an equivalent of one million dollars. The purchase was financed by the Russian philanthropist Vladimir Potanin, who donated funds to Russian Ministry of Culture and ultimately to State Hermitage Museum collection. According to the Hermitage website, this was the largest private contribution to state art museums since the October Revolution.

On 3 November 2008 a work by Malevich entitled Suprematist Composition from 1916 set the world record for any Russian work of art and any work sold at auction for that year, selling at Sotheby’s in New York City for just over $60 million U.S. (surpassing his previous record of $17 million set in 2000).

He was awarded the highest category "1A - a world famous artist" in "United Art Rating".

Malevich in popular culture

Malevich life inspires many references featuring events and the paintings themselves as players. The smuggling of Malevich paintings out of Russia is a key to the plot line of writer Martin Cruz Smith&s thriller Red Square. Noah Charney&s novel, The Art Thief tells the story of two stolen Malevich White on White paintings, and discusses the implications of Malevich&s radical Suprematist compositions on the art world. British artist Keith Coventry has used Malevich&s paintings to make comments on modernism, in particular his Estate Paintings. Malevich&s work is also featured prominently in the Lars Von Trier film Melancholia.

Selected works

1912 Morning in the Country after Snowstorm

1912 The Woodcutter

1912-13 Reaper on Red Background

1914 The Aviator

1914 An Englishman in Moscow

1914 Soldier of the First Division

1915 Black Square and Red Square

1915 Red Square: Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions

1915 Suprematist Composition

1915 Suprematism (1915)

1915 Suprematist Painting: Aeroplane Flying

1915 Suprematism: Self-Portrait in Two Dimensions

1915-16 Suprematist Painting (Ludwigshafen)

1916 Suprematist Painting (1916)

1916 Supremus No. 56

1916-17 Suprematism (1916–17)

1917 Suprematist Painting (1917)

1928-32 Complex Presentiment: Half-Figure in a Yellow Shirt

1932-34 Running Man

(1)Black Square, 1915, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Suprematism.

One of the most famous paintings in Russian art, Black Square marked the turning point of the Russian avant-garde movement. Before creating this painting, Malevich spent eighteen months in his studio, laboring over thirty non-objective paintings. In the end, he had created a series of non-objective paintings, of which Black Square is one. His invention of the word “suprematism” was meant to refer to the supremacy of the new geometric forms. Although the other works in this period were created with visual brushstrokes and asymmetrical forms, Black Square was the prominent piece, with no visual textures and a perfectly symmetrical shape, as it was the paramount of Malevich&s change to pure geometric abstraction: suprematism.

(2)Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918, Museum of Modern Art. Suprematism.

Optimistic about the Russian Revolution, Malevich thought that the newfound freedom wound open the door to a new society, where materialism allowed for spiritual freedom. In his efforts, he studied aerial photography, and this painting is an effort make the the top square seem as if it is floating above the canvas. The stark canvas on White on White it is not devoid of emotion or deep artistic sentiment. Malevich’s brushstrokes are evident, and the soft outlines of the imprecise square make the white austerity of the painting seem more human. When it was created, it was one of the most radical paintings of its day, without reference to any outside reality.

Original Size

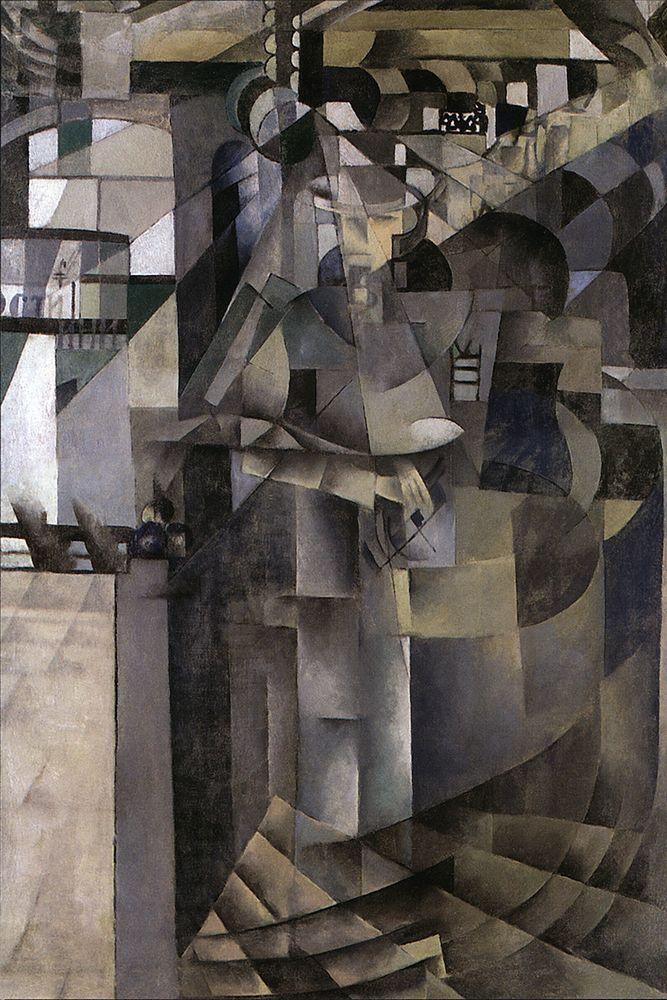

(3)Morning in the Village after Snowstorm, 1913. Cubo-Futurism.

Morning in the Village after Snowstorm is a perfect example of Russian Cubo-Futurism. Not quite cubism, it was a method of portraying object via geometric shapes. This painting was created by Malevich in his earlier career, when his paintings were still representational and he had not clearly delineated his theories of suprematism. Russian art can usually fall within two vast categories: that of a unique artistic style and technique, and that which depicts the social life of the Russian people. Although Malevich’s paintings are often in the first category, this painting does have some elements of social awareness. His depiction of Russian peasants, trudging through a snowstorm, five years before the Russian Revolution, cannot be a mere coincidence.

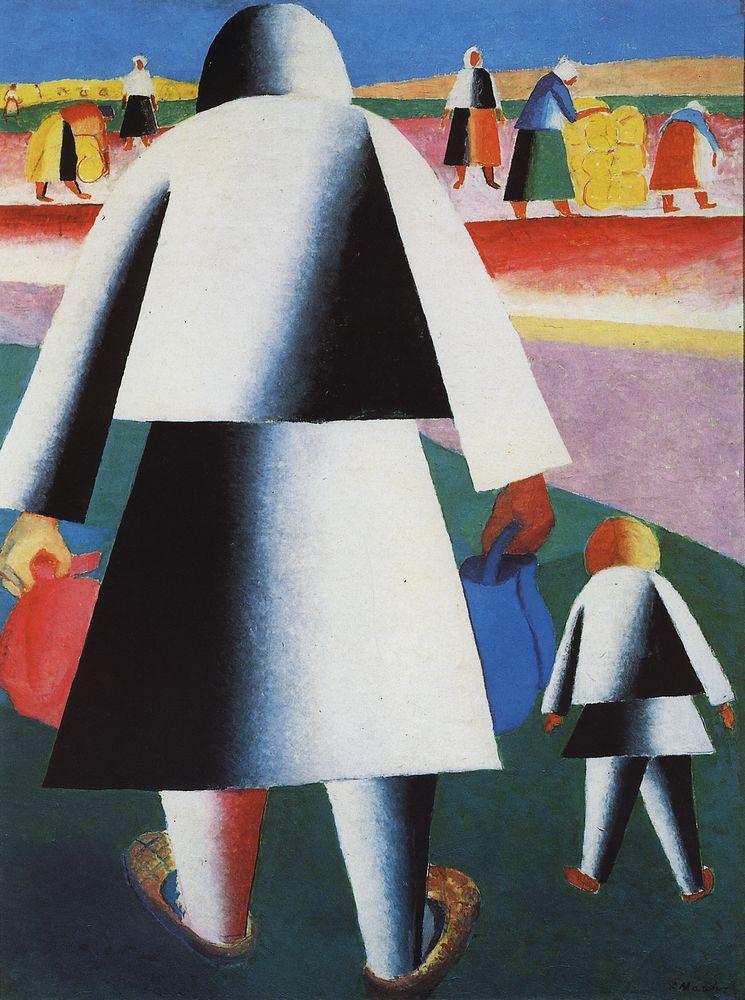

(4)Marpha and Van&ka, 1929, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Suprematism.

(5)Portrait of Ivan Kliun, 1913, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Cubo-Futurism.

(6)Aviator, 1914, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Cubism.

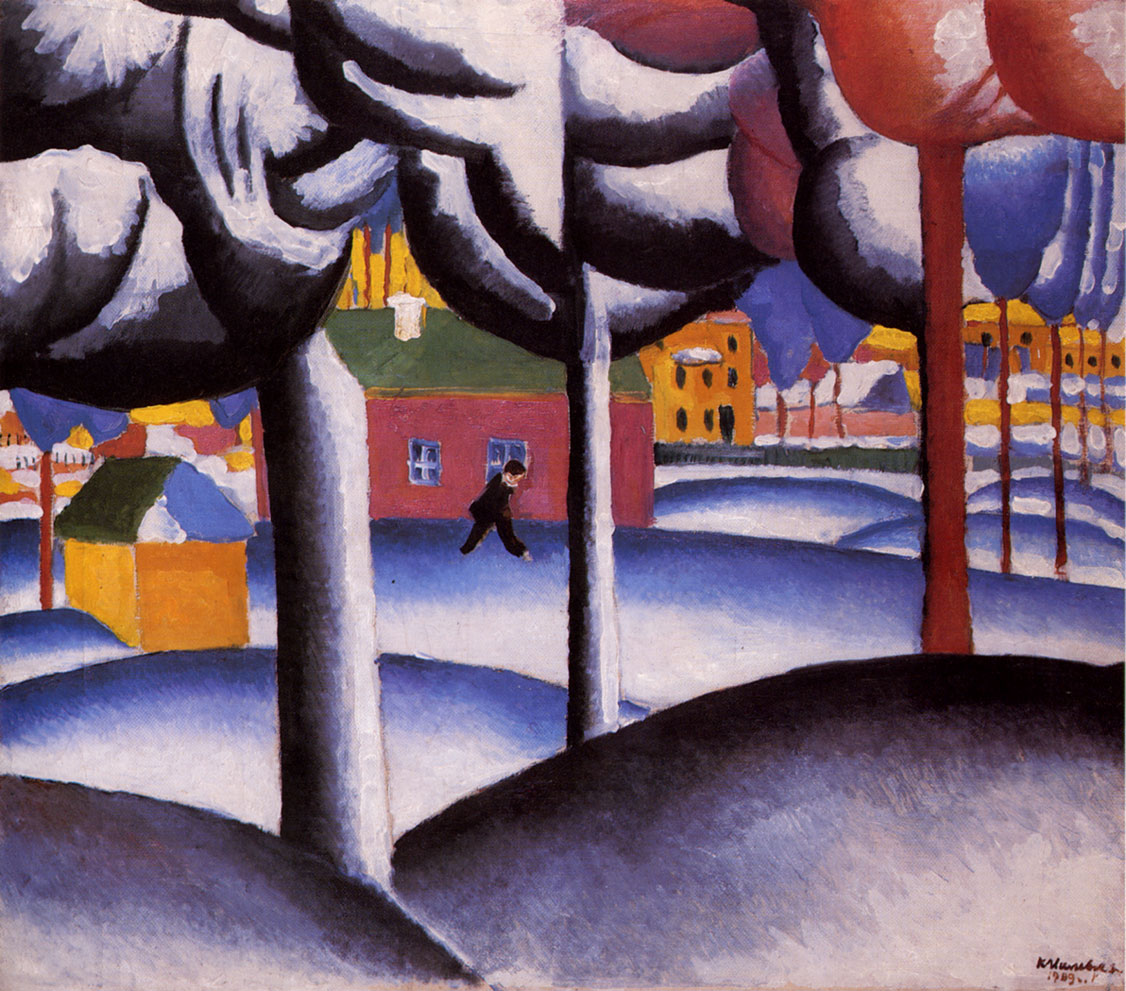

(7)Winter Landscape, 1909, Museum Ludwig. Suprematism.

(8)The wedding, 1907. Post-Impressionism.

(9)Rest. Society in Top Hats, 1908, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Post-Impressionism.

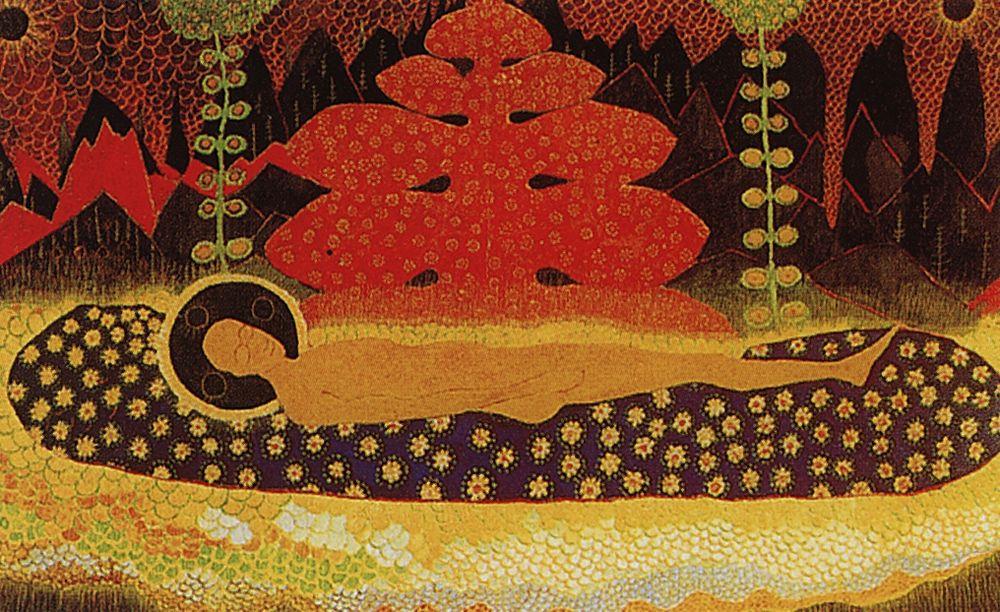

(10)Oak and dryads, 1908. Symbolism.

(11)Veil, 1908, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Symbolism.

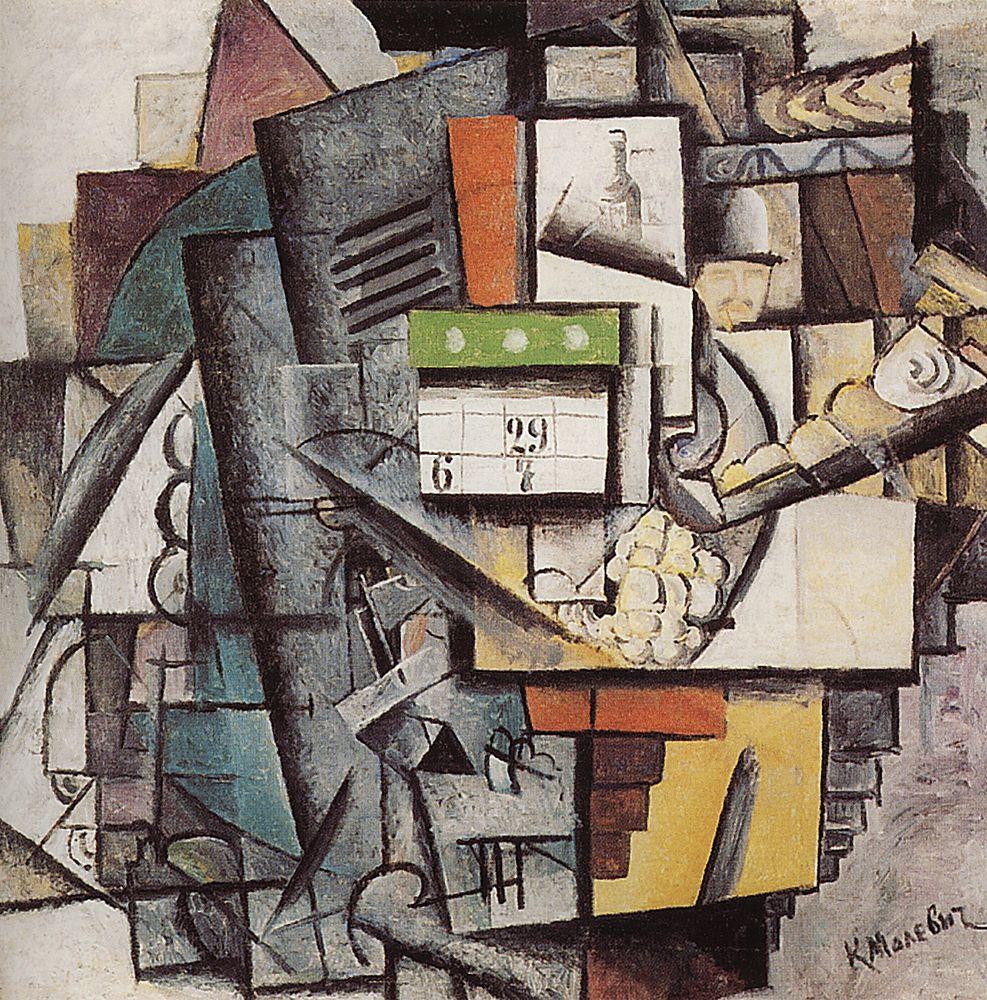

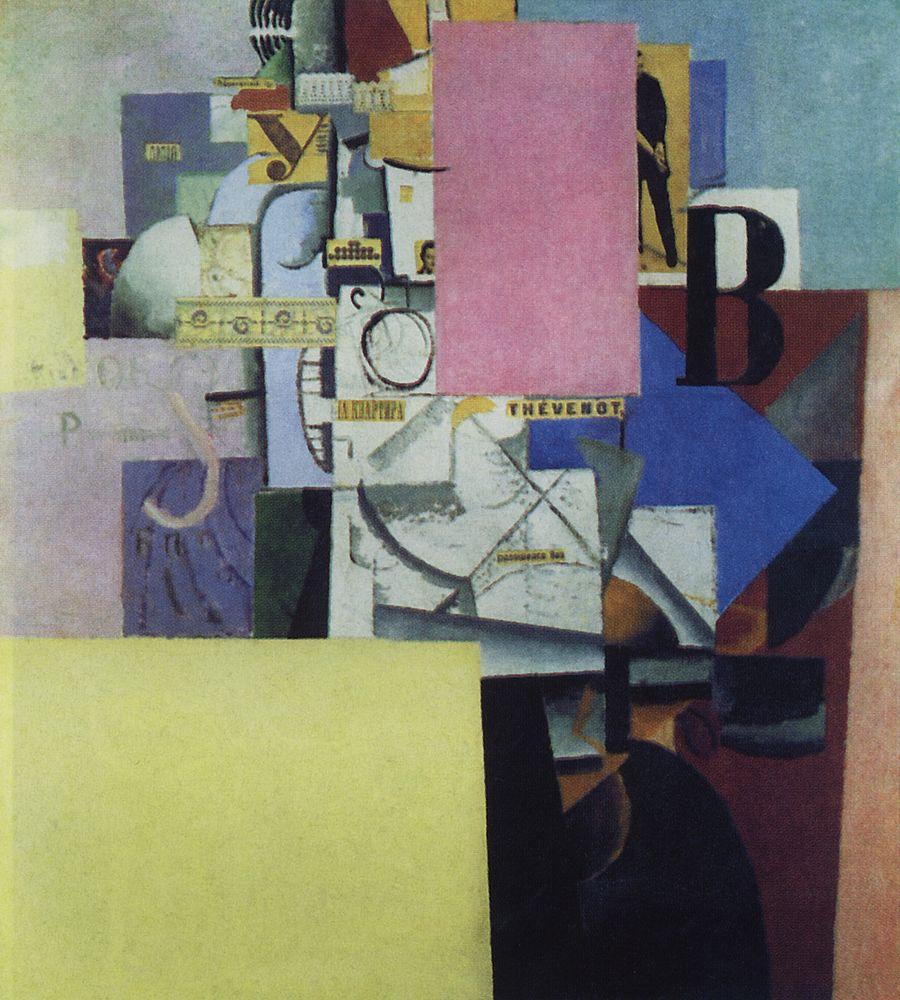

(12)Bureau and Room, 1913, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Cubism.

Original Size

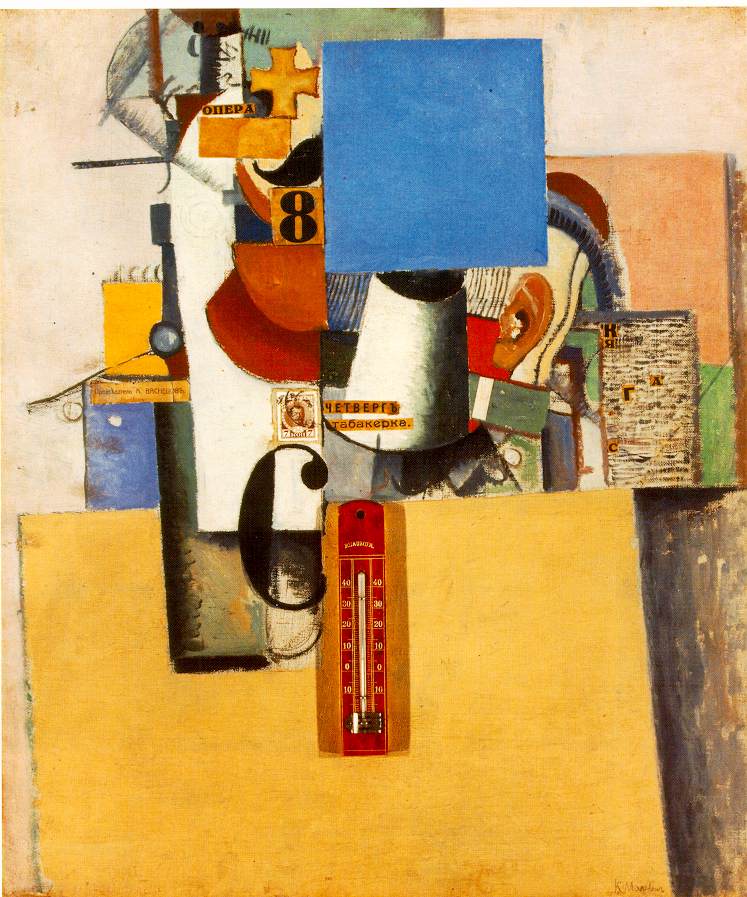

(13)Lady on a Tram Station, 1913, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Cubo-Futurism.

(14)Soldier of the First Division, 1914. Cubism.

(15)Lady at the Poster Column, 1914, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Cubo-Futurism.

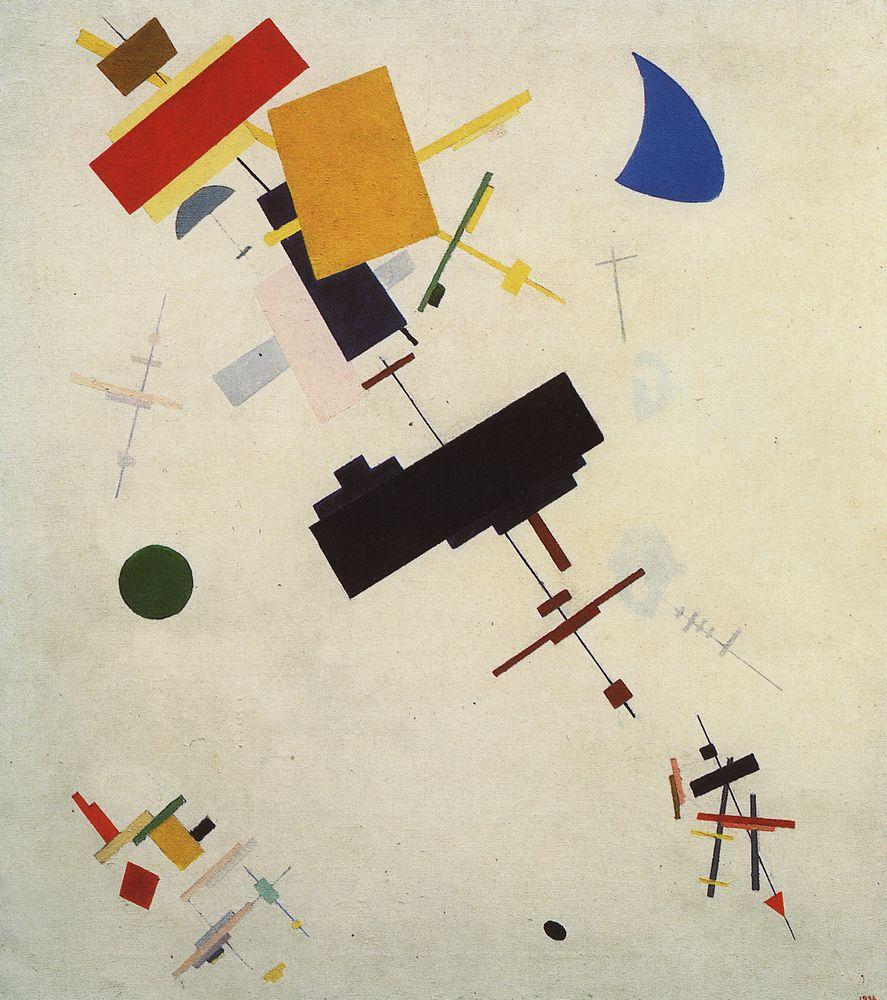

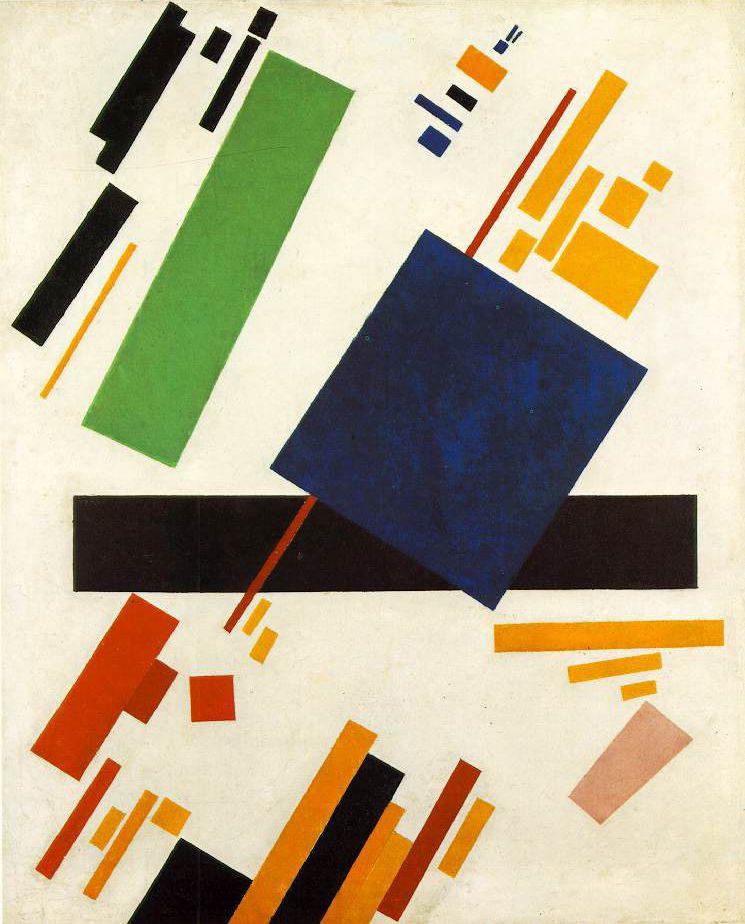

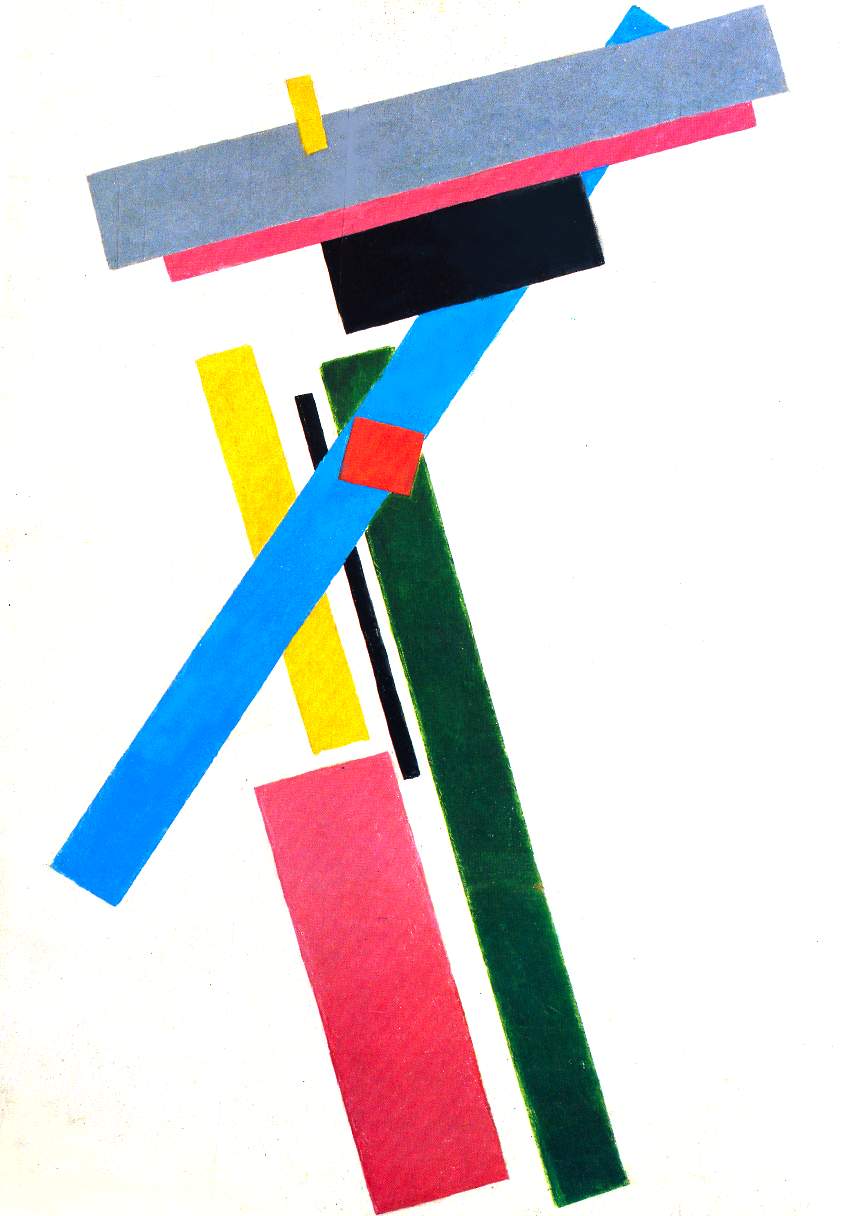

(16)Suprematism, 1915, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Suprematism.

(17)Suprematism, 1916, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Suprematism.

(18)Suprematism, 1916, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Suprematism.

(19)Suprematic Painting, 1916, Suprematism.

(20)Suprematistic Construction, 1915, Suprematism.

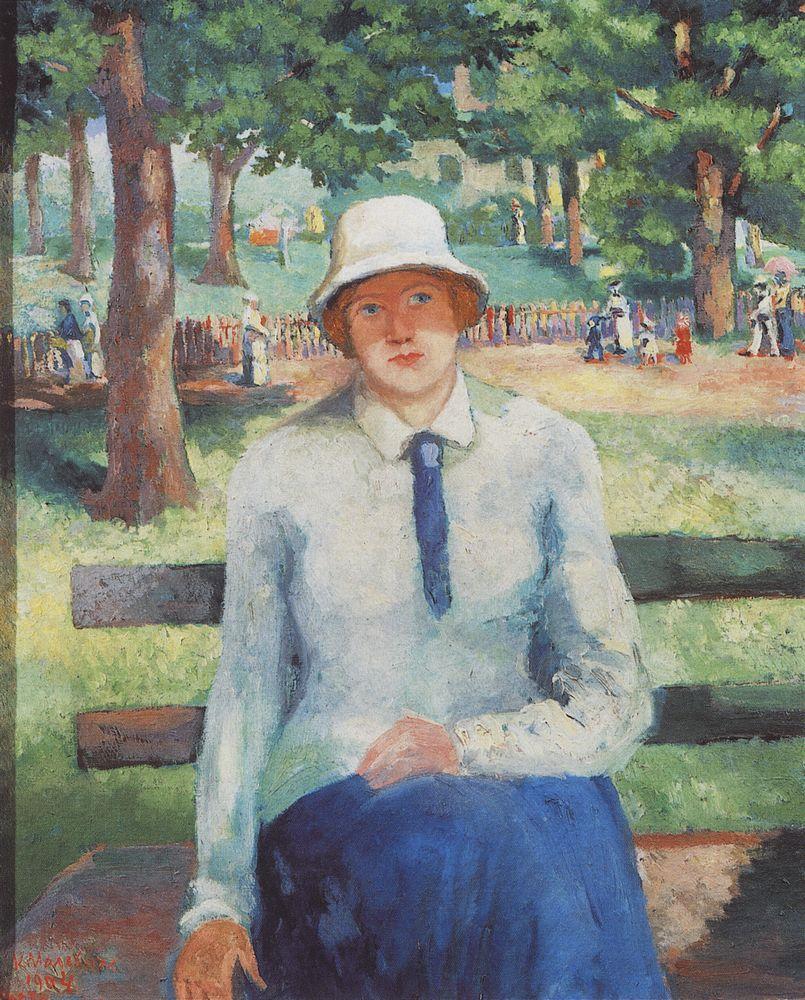

(21)Unemployed Girl, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Impressionism.

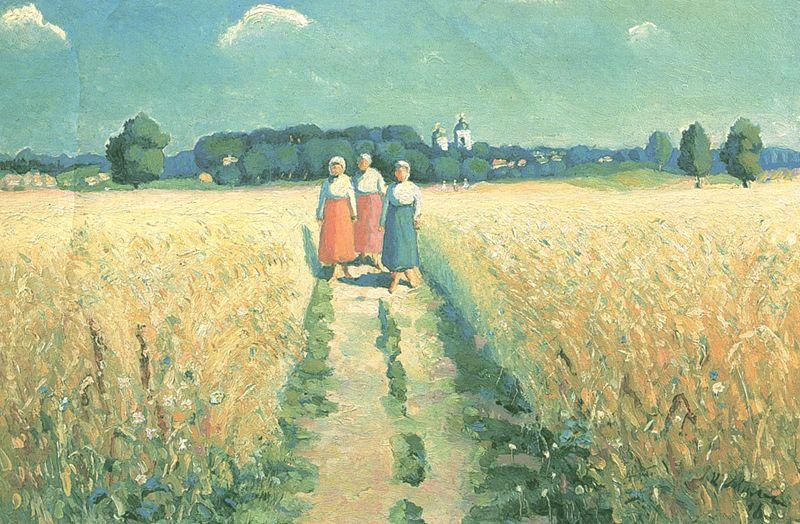

(22)Three women on the road. Impressionism.

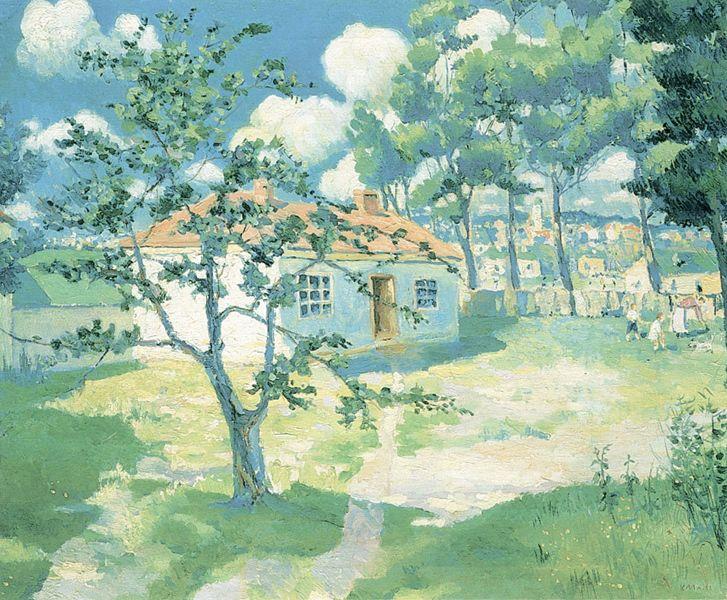

(23)Spring, 1929, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Impressionism.

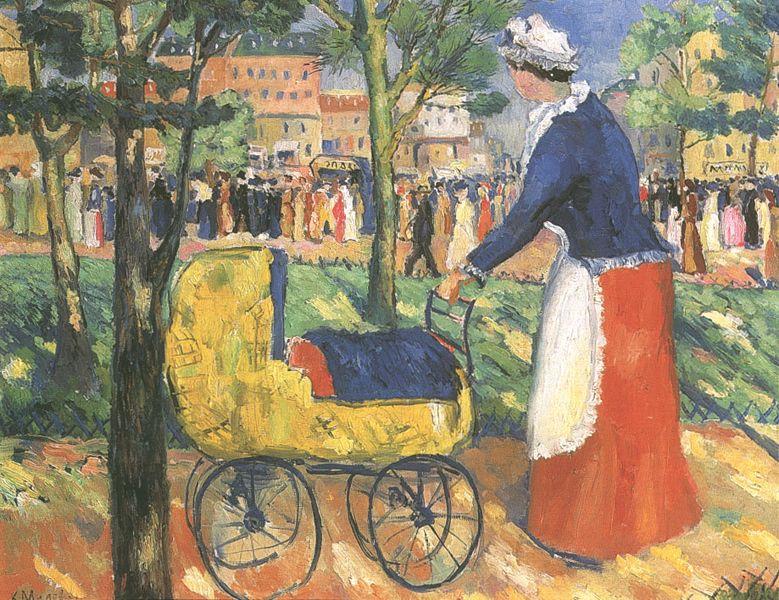

(24)Boulevard, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Impressionism.

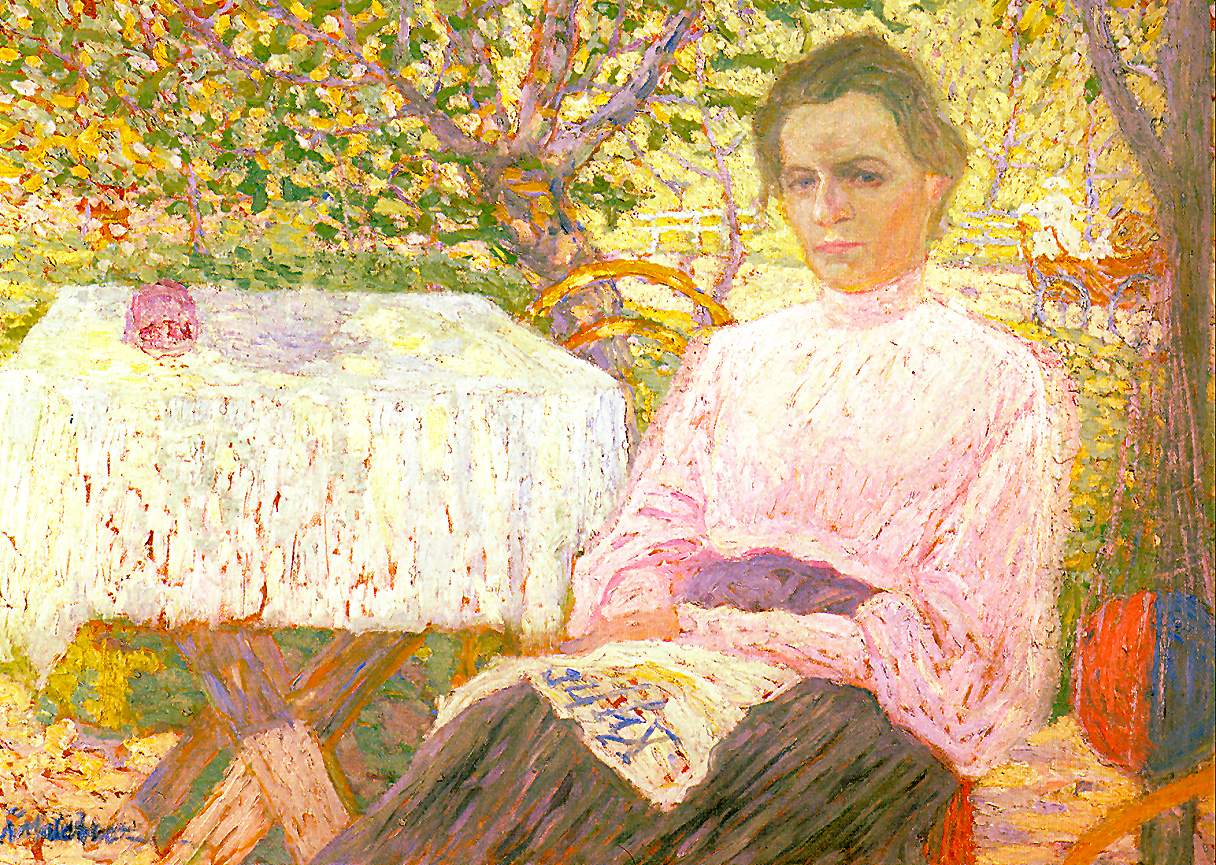

(25)Portrait of a Member of the Artist&s Family, 1906. Pointillism.

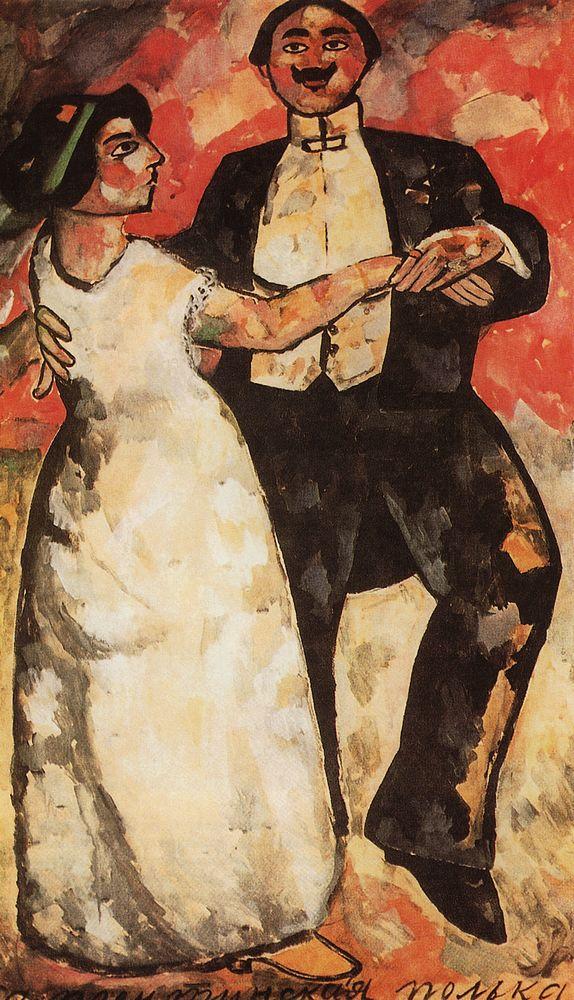

(26)Argentine Polka, 1911. Naïve Art (Primitivism).

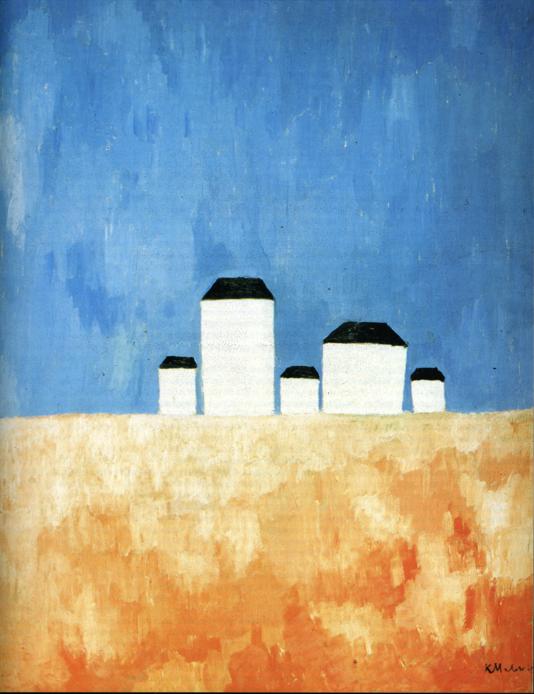

(27)Landscape with Five Houses, 1932, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Suprematism.

(28)Living in a big hotel, 1914. Cubo-Futurism.